““If you want peace of mind, don’t see anyone’s faults. See your own faults.””

Who knows me more than I do? Certainly God and my Guru. Other than them, though, no one knows more about myself than me. Whatever others think of me, whichever way they judge me, they are working with incomplete information. They only see the outside, not what’s inside me. Isn’t the same true, though, when I take it upon myself to judge others?

We all have insufficient information about others (sadly, often even about ourselves) to be able to judge accurately what kind of people they are—even more importantly, what kind of people they will be in the months and years ahead.

If I believe that it is possible for me to be a better version of myself, then shouldn’t I grant the same possibility to others as well? It is best not to indulge in the judgment game (the law of karma takes care of it, who am I to judge?). If I must judge anyone, it had better be my own self.

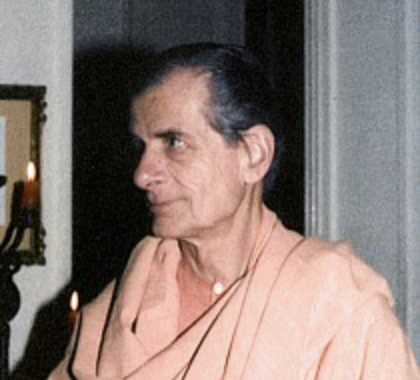

This obvious (but often forgotten) message is conveyed powerfully in the following short essay written by Swami Vidyatmananda (1913–2000), an American monk of the Ramakrishna Order, who joined the Vedanta Society of Southern California in 1950, edited the journal Vedanta and the West, and had sannyāsa in 1964. He later served in the Order’s branch in Gretz, France. A thoughtful essayist and writer, Vidyatmananda is the author of A Yankee and the Swamis. His autobiographical reflections, The Making of a Devotee, are available online.

His essay begins with what had happened “more than 30 years ago,” which today probably means “more than 70 years ago.” Here is the essay:

End of the Story

Swami Vidyatmananda

It had happened more than 30 years ago. I had then been new to the ashrama. It had been my first problem there as resident. Another disciple, X, far senior to me and older, had been behaving in a fashion that other members and I considered scandalous. How could that be? How could it be allowed to go on? Finally I had gone to the Head and complained, expecting the Head to take disciplinary action against the offender. Nothing of the sort! In fact, whatever disciplining had been meted out had been directed toward me myself, as the Head pronounced severely these words: “Never, never judge till you know the end of the story.”

Now, more than a generation later, I recognize that the Head had been right. For recently the story of X had been completed. I’d seen how with the passing years that offending disciple had changed, sweetened, and finally died a saintly death. I held in my hand a letter which X had sent a few days before the end: “How stupid I was in those early days; I didn’t realize it. But thank God our guru never condemned me, and because of his comprehension I somehow gained the courage to keep on. Well, it’s almost finished now. I spend my days repeating my mantra, waiting with tranquility to go Home.”

Casting my mind back to that ancient episode, I felt ashamed. And equally “the end of the story” could mean the end of my own story. That too is what the Head must have meant. For I could see how I was not the same man who had complained against X long before. In these latter years my readiness to judge, to condemn, had quite gone out of me. I had come to see how little exterior signals actually mean. What one takes to be personality traits in others, aspects of their character, revealing actions—on which one bases one’s evaluations—these may disguise more than they reveal. They are like camouflage or protective coloration obscuring the truth.

“Do we ever,” I had asked myself in recent years, “do we ever have an inkling of what goes on inside other people? Who knows what fear, what sense of inadequacy, what hunger to be loved, what need for recognition form the visage with which people face the world?” I was so sure of my own conscientiousness and yet so ready to discover its lack in another. I know the end of my own story, or practically so, and I can see clearly that judging others is something no one who is in the least wise should ever dare to do.

There was another paragraph in X’s letter: “As this may be the last time I shall be able to write to you, I wish to make a confession. All those years ago when you first came to the ashrama some of us found the things you did shocking. I seriously considered complaining to the Head about you, but then I remembered that he was fond of saying, ‘Never, never judge until you know the end of the story.’ So I’m glad I didn’t. As I have watched your development these three decades and seen what a devotee you have become, I know that such an early evaluation would have been hasty and wrong. I’m sorry I ever had such feelings.”

I read these lines with burning cheeks.